Echoes of ARPANET: From Distributed Communications to Distributed Proof

The 60-year-old design philosophy that compliance regulations are now demanding.

ARPANET was built because centralized systems break. Sixty years later, compliance regulations are demanding the same fix.

The Two-Letter Accident That Built the Modern World

At 10:30 PM on October 29, 1969, a twenty-one-year-old UCLA graduate student named Charley Kline sat down at an SDS Sigma 7 terminal and tried to type the word “LOGIN.”

He got two letters out.

The system crashed. The connection between UCLA and the Stanford Research Institute, 350 miles of leased telephone line, died after transmitting the letters L and O.

The first message ever sent across what would become the internet was, by accident, “lo.” As in lo and behold.

An hour later, the connection succeeded. Nobody wrote a press release. But those two letters, transmitted between two refrigerator-sized computers in two California basements, planted the seed for a network that now connects 30 billion devices and underpins a global economy worth over $110 trillion .

Here is the part of that story most people get wrong: ARPANET was not built because someone had a vision of email, e-commerce, or social media. It was built because the United States government realized its entire military communications infrastructure could be severed by a single coordinated attack on a handful of telephone switching centers, and a nation that cannot communicate cannot coordinate a response. The problem wasn’t the weapons. The problem was that the communications network had a fragile, centralized architecture that made it an irresistible target.

ARPANET was not a product of optimism. It was a product of existential dread.

That same structural logic is playing out again. A threat severe enough to force the invention of distributed, fault-tolerant infrastructure. The threat is not thermonuclear war. It is the converging wave of regulatory compliance bearing down on the most valuable asset class on earth: data.

And the timeline is not theoretical. MiCA enforcement begins July 2026. The EU AI Act’s high-risk obligations take effect August 2026. DSCSA pharmaceutical traceability requirements hit in November 2026. EU Battery Regulation digital passports arrive February 2027. CSDDD transposition follows in July 2028. Each regulation demands capabilities that centralized data systems structurally cannot provide: immutable provenance, cross-jurisdictional auditability, privacy-preserving transparency, and automated compliance enforcement.

The global big data and analytics market reached roughly $350 billion in 2024 and is projected to approach $445 billion this year. The five largest U.S. hyperscalers alone are set to spend between $660 and $690 billion on AI-related capital expenditure in 2026, nearly doubling 2025 levels. And every byte of that value sits on centralized architectures that regulators are now systematically declaring insufficient.

The enterprises that recognized this pattern early are already building. The rest are running out of runway.

The Man Who Tried to Save the World with a Fish Net

The intellectual father of the internet was not a computer scientist. He was an electrical engineer at the RAND Corporation named Paul Baran, and his obsession was not technology. It was the mathematics of survival.

The year was 1960. The nuclear arms race was accelerating, but Baran’s concern was not the weapons themselves. It was the communications network that everything depended on.

America’s entire military command infrastructure ran through the AT&T telephone network. That network used a centralized star topology: calls routed through a small number of major switching centers. Destroy those centers, and the nation goes silent. A targeted strike against a handful of switching hubs would sever the ability to coordinate any response at all. And in Cold War strategy, a nation that cannot communicate cannot deter. The vulnerability wasn’t theoretical. It was architectural.

Baran spent four years developing a radical alternative. In 1964, he published “On Distributed Communications,” eleven memoranda for the U.S. Air Force that reimagined communications architecture from the ground up. Instead of building a few heavily fortified central switches (the expensive, “gold-plated” approach) he proposed building many cheap, unreliable nodes connected in a mesh, like a fisherman’s net. Messages would be broken into small blocks and routed dynamically through whatever paths remained open after an attack. If one node was destroyed, traffic would flow around the gap like water around a stone.

He called it “hot-potato routing.” The design philosophy was what mattered: Baran did not try to prevent failure. He assumed failure was inevitable and designed a system that worked through it.

His cost estimate: $60 million for 400 switching nodes serving 100,000 users. Adjusted for inflation, roughly $600 million. Less than Meta paid in a single GDPR fine.

The Most Expensive “No” in History

Baran took his proposal to AT&T. The response has become one of the most consequential rejections in technology history:

“It can’t possibly work. And if it did, damned if we are going to set up any competitor to ourselves.”

They were not stupid. They were incumbents. Incumbents optimize the system they have. They do not replace it with something that makes their expertise irrelevant.

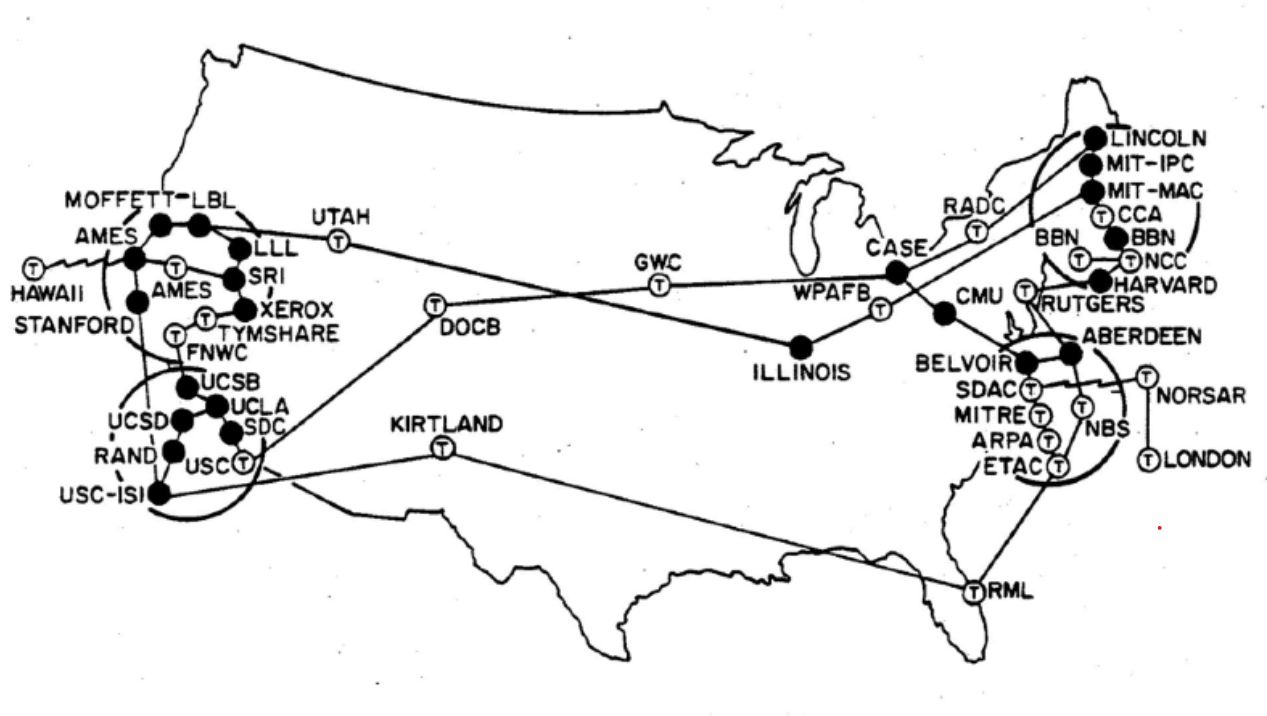

It took ARPA, the Defense Department’s Advanced Research Projects Agency, to act. By December 1969, four nodes were operational. By 1973, forty. Then came the inflection point.

January 1, 1983. “Flag Day.”

Every node on ARPANET simultaneously switched from NCP to TCP/IP. Before Flag Day, ARPANET was a research curiosity. After Flag Day, it was a universal platform. Commercial restrictions lifted in 1991. Mosaic launched in 1993. Today, those four nodes are 30 billion connected devices.

The pattern: Existential threat → distributed architecture → exponential adoption.

It has happened before. It is happening again. And the near-miss that almost prevented it from mattering at all happened the same year as Flag Day, in a bunker outside Moscow.

The Man Who Saved the World by Not Trusting the Machine

Eight months after Flag Day, at 12:14 AM on September 26, 1983, a screen inside a secret Soviet bunker south of Moscow flashed a single word in angry red letters: “LAUNCH.”

Lieutenant Colonel Stanislav Petrov, a software engineer who had helped build the early-warning system he was now monitoring, watched the Oko satellite network report that one American Minuteman ICBM had launched from Malmstrom Air Force Base in Montana. Seconds later, four more appeared. Five inbound nuclear warheads. The system declared “high reliability.”

Petrov had roughly ten minutes to decide the fate of civilization.

The protocol was unambiguous: report the launch up the chain of command. Soviet leadership, already on hair-trigger alert after shooting down Korean Air Lines Flight 007 three weeks earlier, would almost certainly order a retaliatory strike. Hundreds of warheads. Hundreds of millions dead on the first day. A billion within months.

But Petrov hesitated. Something was wrong with the data.

He had been trained that a genuine American first strike would involve hundreds of simultaneous launches, not five. Ground-based radar showed nothing. And he knew, as only a systems engineer could, that the Oko satellites were new, imperfect, and prone to errors that the software had not yet been trained to filter.

Petrov made a decision that violated every protocol he had been given. He reported the alarm as a false alarm.

He was correct. The satellites had mistaken sunlight reflecting off high-altitude clouds for missile plumes. A rare alignment of solar angle and orbital trajectory had created phantom warheads. The system was subsequently rewritten to cross-reference multiple data sources. But on that night, the only cross-reference was a single human being’s judgment that the data was wrong.

The Cold War almost ended in nuclear annihilation not because of aggression, but because of a data integrity failure in a centralized system that trusted its own sensors. One satellite constellation. One data stream. One bunker. One officer. No verification. No corroboration. No distributed consensus. The Oko system had the same architectural flaw Baran had identified two decades earlier, and the same flaw AT&T’s telephone network had: a centralized design where a single point of failure could cascade into catastrophe. The problem Baran tried to solve in 1964, ensuring that critical information could be verified across multiple independent sources, remained unsolved in 1983.

Petrov should not have needed to be a hero. The system should have verified itself.

That sentence, the system should have verified itself, is the design philosophy that connects Paul Baran’s fish net in 1964, the first ARPANET message in 1969, the Oko failure in 1983, and the enterprise blockchain infrastructure being deployed right now in 2026. Baran designed networks where communications survive the destruction of any individual node. Blockchain builds ledgers where data integrity survives the failure of any individual actor. The through-line is architectural: when the stakes are high enough, you do not design systems that depend on someone doing their job correctly. You design systems that prove themselves.

The World’s Most Valuable Asset on the World’s Most Vulnerable Architecture

ARPANET was built to protect the flow of military commands. Baran’s distributed architecture ensured that information would survive when everything else was destroyed. Sixty years later, information has not merely survived. It has become the dominant economic asset of human civilization.

The comparison to oil isn’t perfect (nobody heats a building with a dataset) but the economic logic holds. Data is infinitely reusable: a single dataset can train an AI model, personalize a customer experience, optimize a supply chain, and satisfy a regulatory filing, simultaneously, without degradation. It is ubiquitous, accessible across continents without diminishment. It is exponentially valuable, because combining datasets creates intelligence that no individual dataset provides alone. The top global companies by market cap (Apple, Microsoft, Alphabet, Amazon, Meta) derive dominance not from physical plants but from data ecosystems.

Yet this asset sits on centralized architectures that Paul Baran and Stanislav Petrov would both recognize as fatally flawed. Centralized databases. Single-cloud deployments. Star topologies where one breach, one misconfigured portal, one missing authentication layer can expose hundreds of millions of records. GDPR enforcers have levied €7.1 billion in cumulative fines since 2018. The Change Healthcare breach exposed 192.7 million patient records through a single Citrix portal lacking multi-factor authentication.

The regulatory response is not abstract. It is a compliance wave with hard deadlines:

| Regulation | Deadline | Core Requirement |

|---|---|---|

| MiCA | July 2026 | Digital asset compliance infrastructure |

| EU AI Act (high-risk) | August 2026 | Verifiable AI governance and decision logging |

| DSCSA | November 2026 | Pharmaceutical supply chain traceability |

| EU Battery Regulation | February 2027 | Digital battery passports with full provenance |

| CSDDD transposition | July 2028 | Corporate sustainability due diligence |

These are not aspirational guidelines. They are enforceable mandates with penalties that can reach into the billions. And they share a common thread: each one requires organizations to prove the integrity, provenance, and governance of their data. Not assert it. Prove it. Cryptographically, immutably, across jurisdictions.

Centralized systems were not designed to do this. They were designed to store, process, and serve data. Proving that data has not been altered, that decisions followed policy, that governance actually happened at every node in the chain: that is a fundamentally different architectural requirement. It is the same gap Baran identified in 1960, when the question was not “can we send a message?” but “can we guarantee a message survives?”

In the late 1950s, American intelligence believed the Soviets had far more ICBMs than they actually possessed, the famous “missile gap.” The data was centralized, unverifiable, and subject to political interpretation. The gap turned out to be largely fictional, confirmed only later by satellite reconnaissance. Enterprises operating on mutable, siloed, unverifiable data face their own version of this problem: strategic decisions built on data they cannot prove is accurate, complete, or untampered. Compliance regulations are now demanding they close that gap, with deadlines measured in months, not years.

What Verified Infrastructure Actually Looks Like

History is useful, but only if it clarifies the present. The structural argument (serious enough threat demands distributed architecture) needs concrete evidence. Several deployments already demonstrate what happens when organizations stop trusting their data and start proving it.

Six days, eighteen hours, and twenty-six minutes. That’s how long it used to take Walmart to trace a mango back to its source farm. On a blockchain-verified supply chain, the same trace takes 2.2 seconds.

But the speed is almost beside the point. The real shift is that the same provenance dataset (origin, handling, temperature, transport, supplier identity) now feeds supplier scoring models, insurance underwriting, logistics optimization, regulatory reporting, and ESG audits across more than 200 suppliers and twenty-five product categories. One record, generated at the point of harvest, doing the work of a dozen separate data collection efforts. The data doesn’t deplete with use. It compounds.

JP Morgan’s Kinexys tells a different kind of story. Over $2 trillion in cumulative notional value processed, $2-3 billion daily, 10x year-over-year growth. The raw settlement speed matters. But what’s actually interesting is the layering effect: on-chain settlement data feeds collateral management, which feeds FX operations, which feeds tokenized asset services. Each layer amplifies the one beneath it. When Kinexys expanded to London with GBP settlement in 2025 and launched on-chain FX settlement, it wasn’t building a new product from scratch. It was extending an infrastructure that already existed because the payment data was already verified, already on-chain, already trusted. Competitors would need to start at zero.

The EU Battery Regulation doesn’t take effect until February 2027. Circulor didn’t wait. It launched the world’s first commercially available digital battery passport on the Volvo EX90, tracking cobalt, lithium, nickel, and mica from mine to car across 150 million battery cells with over 20 billion traceability data points. The platform now serves 52% of global cell manufacturers, including Polestar, Volkswagen, and Mercedes-Benz. Every competitor entering this space will measure itself against Circulor’s data model, provenance schema, and verification logic. That’s the difference between meeting a regulation and defining what compliance means for an entire industry.

Global shipping has a paperwork problem that costs the industry billions. GSBN attacked it head-on: over 700,000 electronic Bills of Lading issued across a network handling one in three containers moved worldwide. Cargo release that used to take 2-3 days now takes 1-2 hours. McKinsey pegs industry-wide eBL adoption at $6.5 billion in potential direct savings. The trade data flowing through GSBN’s network, vessel schedules, cargo manifests, financing terms, customs declarations, creates a shared intelligence layer that no single shipping line could build or afford on its own.

At 30,000 feet, a counterfeit turbine blade doesn’t trigger a compliance finding. It triggers a catastrophe. Honeywell built GoDirect Trade around that reality: an aerospace parts marketplace where every component’s full maintenance and ownership history is cryptographically verified on-chain. The result isn’t just an authenticity solution. It’s the benchmark other aerospace suppliers now have to meet for verifiable provenance.

Each of these deployments planted a flag: this is what verified data infrastructure looks like in this industry. Build to this standard or explain to regulators why you didn’t.

Worth acknowledging: enterprise blockchain has had its share of false starts. Plenty of “proof of concept” announcements between 2017 and 2022 went nowhere. The difference now is that regulatory deadlines have replaced voluntary experimentation. Compliance obligations with billion-euro penalties create deployment urgency that no amount of conference keynotes ever could.

And here’s what makes the current moment different from even two years ago: AI is now making operational decisions across every one of these organizations. Pricing, risk scoring, claims adjudication, credit underwriting. The EU AI Act’s high-risk obligations, effective August 2026, will require verifiable proof that automated decisions followed the rules. The enterprises that can prove every AI-driven decision was logged, verified, and compliant won’t just meet the regulation. They’ll define what AI governance looks like for their sectors, and their competitors will spend years catching up to a standard they had no hand in shaping.

Baran’s Insight, Rebuilt for Regulatory Survival

The pattern embedded in every one of these deployments is the same pattern Baran discovered in 1964 and Petrov’s near-catastrophe exposed in 1983: trust is a liability. Verification is infrastructure.

Baran did not try to make central switches blast-proof. He eliminated the need for them. Petrov’s system failed because it trusted a single data source without cross-referencing. The Oko software was rewritten afterward to verify across multiple systems, the same principle that blockchain consensus mechanisms enforce by design.

This is the infrastructure BlockSkunk builds.

Not zero-trust as a network security buzzword. Zero-trust as a governance philosophy: verify everything, trust nothing by default, prove every action. The layer between an organization’s existing systems and the regulatory obligations those systems cannot handle alone.

Automated Compliance. AI monitors regulatory changes across jurisdictions. Maps them to an organization’s specific obligations. Generates reports before a human opens a spreadsheet. As MiCA, the EU AI Act, DSCSA, and the Battery Regulation deadlines converge in the months ahead, compliance cannot be a quarterly exercise run by a team with spreadsheets. It has to run continuously, updating in real time as regulations evolve. BlockSkunk’s infrastructure does exactly this: continuous monitoring, automatic mapping, audit-ready reporting.

Immutable Audit Trails. Every transaction. Every decision. Every policy enforcement, recorded on a permissioned ledger that no one can alter. Not the company. Not a rogue employee. Not even BlockSkunk. When GDPR enforcers levy billion-euro fines and the EU AI Act demands proof that automated decisions followed the rules, the question is not “did compliance happen?” The question is “can you prove it?” An immutable ledger answers that question before an auditor asks it.

Verifiable Governance. Board directives, operational policies, risk controls: enforced and proven at the infrastructure layer. The architecture demonstrates compliance, independent of any individual or document. For enterprises preparing for GENIUS Act and MiCA reporting, financial institutions modernizing compliance infrastructure, or networks pursuing CMMC compliance, this is the difference between asserting governance and demonstrating it cryptographically.

14 weeks from assessment to audit-ready production. BlockSkunk maps every governance gap, regulatory exposure, and trust dependency in an organization’s existing systems. Identifies every point where the organization currently trusts instead of verifies. Then closes each one. What typically takes 18-24 months of blockchain deployment compresses to 90-120 days, fully managed, with compliance built in from day one rather than bolted on afterward.

Baran designed around communications failure. Petrov’s ordeal proved why verification cannot depend on a single human in a bunker. BlockSkunk designs around regulatory failure, with AI that monitors, blockchain that proves, and governance that verifies itself. The structural logic is identical. The stakes, for any enterprise managing significant data assets as these compliance deadlines approach, are no less urgent.

Lo

Paul Baran put his distributed network design in the public domain. He could have patented it. He chose not to.

His $60 million design for 400 switching nodes became the foundation of a $110-trillion economy. Stanislav Petrov’s ten-minute decision in a bunker outside Moscow ensured there was still a civilization left to build it on. The telephone monopoly that dismissed Baran was dismantled. The satellite system that nearly killed us all was rewritten to verify before it trusted.

The threat has changed. Centralized communications failures became centralized data failures, and the penalties shifted from strategic vulnerability to regulatory fines denominated in billions. The architecture has evolved. Packet switching became permissioned ledgers with AI-driven compliance monitoring and cryptographic proof of governance. The incumbents dismissing it sound almost exactly like AT&T’s engineers in 1964.

But the structural logic has not changed. When the stakes are high enough, the architecture must be distributed. When failure is inevitable, the system must work through failure, not despite it. When an asset is valuable enough to attract billion-euro fines, it demands infrastructure that proves itself.

The first ARPANET message was an accident. Two letters before a crash. What followed was architecture. What followed after that was a world rebuilt on distributed infrastructure that the incumbents said was impossible.

The compliance deadlines are not waiting. The question is whether to build the infrastructure now, or explain later why it wasn’t there.

BlockSkunk builds zero-trust governance infrastructure for regulated industries. Your organization runs on trust. It should run on proof.

Schedule a 30-minute assessment to map every point where your organization trusts instead of verifies, and see what audit-ready compliance infrastructure looks like: blockskunk.com/demo